Introduction

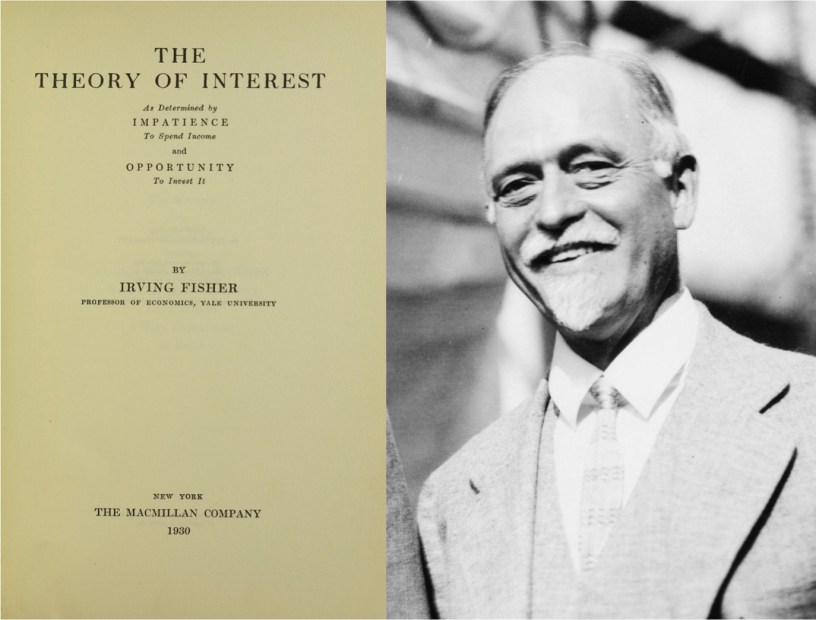

Few economists have left as enduring a mark on both theory and practice as Irving Fisher. Writing in the first decades of the twentieth century, Fisher straddled the world of late classical political economy and the emerging formal neoclassical economics. His book The Theory of Interest (1930) was his culminating effort to synthesize decades of work on capital, interest, and intertemporal choice. It sought to unify the long-standing debates on the determinants of interest into a single analytical framework. Fisher argued that interest is fundamentally an equilibrium outcome between individuals’ preferences for present versus future consumption and the investment opportunities that transform present resources into future income.

The work is notable not only for solving long-standing theoretical disputes but also for shaping the foundations of modern finance, macroeconomics, and central banking. Yet, it also has limitations, reflecting its assumptions of perfect foresight, neglect of uncertainty, and abstraction from institutional structures. This essay analyzes and assesses the significance of The Theory of Interest, situating it within the intellectual traditions Fisher inherited, detailing its major contributions, exploring its critiques, and evaluating its long-term legacy.

Historical Background

The problem of interest had long occupied economists. In classical economics, figures such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo largely treated interest as the return to capital, a distributive share determined by productivity. John Stuart Mill introduced the idea of abstinence or waiting as a justification for interest, though he lacked a rigorous analytical structure.

In the late 19th century, Eugen Böhm-Bawerk advanced the Austrian theory of capital and interest, emphasizing “roundaboutness” in production. He argued that more time-consuming production processes tended to be more productive, and interest represented the return to waiting for these longer processes to mature. This theory heavily stressed the physical productivity of capital but faced difficulties in dealing with the subjective preferences of individuals.

Marshall and other neoclassicals, meanwhile, attempted to bring demand and supply frameworks to bear on interest, but the treatment was incomplete. By the early 20th century, economists faced two broad approaches: one that emphasized the productivity of capital (objective) and one that emphasized time preference (subjective). What was missing was a unified synthesis that explained interest as the interaction of both.

Fisher inherited this intellectual puzzle and, drawing on both Böhm-Bawerk and Marshall, set out to develop a formal and systematic explanation of interest. His earlier works (The Rate of Interest, 1907; The Nature of Capital and Income, 1906) laid the groundwork, but The Theory of Interest (1930) represented the mature statement of his ideas.

The Theory of Interest: Core Contributions

Intertemporal Choice and Time Preference

Fisher’s most original contribution was to model consumption as an intertemporal choice. Individuals, he argued, face decisions about whether to consume today or save and consume in the future. Their preferences are shaped by impatience(time preference): a psychological inclination to prefer present goods over future goods. Fisher formalized this with indifference curves that represented different combinations of present and future consumption.

This insight anticipated much of modern microeconomics. Intertemporal choice is now a standard framework for analyzing savings behavior, consumption smoothing, and investment decisions. Fisher’s graphical and mathematical treatment of time preference helped shift interest theory from abstract discussion to operational analysis.

The Investment Opportunity Frontier

Fisher also introduced the concept of an investment opportunity frontier. Just as production theory deals with transforming inputs into outputs, intertemporal economics involves transforming present resources into future ones. Investment can increase future consumption, but with diminishing returns.

By combining individual indifference curves with the investment opportunity frontier, Fisher could show how an equilibrium interest rate arises: it is the rate at which households’ willingness to trade present for future consumption intersects with the economy’s ability to transform present goods into future goods.

Equilibrium Interest Rate Determination

Fisher’s synthesis was elegant:

- Time preference (demand for future goods) pulls the interest rate upward if people are very impatient.

- Investment opportunities (supply of future goods) push the interest rate downward when opportunities for profitable investment are abundant.

The equilibrium interest rate balances these forces. This solution resolved the earlier theoretical conflict between productivity and abstinence theories. Neither alone explained interest; rather, both were necessary.

Real vs. Nominal Interest Rates: The Fisher Equation

Perhaps Fisher’s most enduring contribution was his distinction between real and nominal interest rates. He argued that lenders and borrowers care about real purchasing power, not just nominal sums. Thus, the nominal rate (i) reflects both the real rate (r) and expected inflation (π^e):

i = r + π^e

This “Fisher Equation” remains fundamental in monetary economics and policy. Central banks, investors, and analysts use it routinely to adjust for inflation expectations. Its clarity in separating money from real variables was a decisive advance over classical and Austrian theories.

Graphical and Mathematical Tools

Fisher’s work also advanced the methodological toolkit of economics. His use of indifference curves, production frontiers, and equilibrium analysis foreshadowed modern general equilibrium theory. While his mathematics was simple by today’s standards, it represented a significant advance in formalizing capital and interest.

Assessment of the Work

Microeconomic Foundations

By grounding interest in intertemporal utility maximization, Fisher gave the phenomenon a firm microeconomic basis. His approach unified subjective psychology (time preference) with objective technology (investment productivity). This synthesis later influenced the development of Ramsey’s optimal savings model (1928) and Solow’s growth model (1956).

Influence on Modern Finance

The principle of discounting future income flows to their present value, central to corporate finance and investment analysis, flows directly from Fisher’s theory. The net present value (NPV) criterion, capital budgeting, and asset pricing models all rest on Fisherian foundations.

Relevance for Monetary Theory and Central Banking

The Fisher Equation is now embedded in monetary policy practice. Central banks target real interest rates, adjusting for inflation expectations, to guide investment and consumption. This simple but profound distinction between real and nominal rates clarified monetary debates that had previously been muddled.

Integration of Capital and Utility Theory

Fisher’s ability to integrate capital theory with utility theory was a major intellectual achievement. By treating capital as a stock of productive opportunities and consumption as a stream of satisfactions, he bridged the divide between objective and subjective approaches.

Critiques and Limitations

Despite its brilliance, The Theory of Interest was not without shortcomings.

- Perfect Foresight Assumption

Fisher assumed agents know future investment returns and inflation with certainty. In reality, uncertainty, risk, and expectations are fundamental. Later theories—Keynes’s liquidity preference, Hicks’s IS-LM framework, and modern asset pricing with risk premia—addressed this gap. - Neglect of Institutional Context

Fisher abstracted from banks, credit markets, and liquidity constraints. By treating interest purely as an equilibrium price, he overlooked the role of money, credit cycles, and financial instability. Keynesians and institutional economists later emphasized these dimensions. - Short-Run vs. Long-Run Validity

The Fisher Equation holds robustly in the long run, but short-run deviations occur because inflation expectations adjust sluggishly. Empirical studies often find that nominal rates respond imperfectly to inflation in the short run. - Behavioral Critiques

Modern behavioral economics questions the assumption of consistent time preference. Evidence shows that individuals often display hyperbolic discounting, irrational impatience, or myopia, complicating Fisher’s rational framework.

Legacy and Long-Term Significance

Influence on Growth Theory

Frank Ramsey’s 1928 model of optimal savings, contemporaneous with Fisher, shared a similar structure but extended it to the social planner context. Later, Solow and Cass-Koopmans growth models relied on intertemporal optimization, drawing conceptually from Fisher’s framework.

Modern Financial Economics

From capital asset pricing to option valuation, Fisher’s principle of discounting is fundamental. The valuation of bonds, stocks, and projects all depend on the intertemporal trade-offs he analyzed.

Central Banking and Inflation Targeting

The Fisher Equation underpins modern inflation-targeting regimes. By focusing on real interest rates, central banks can separate the effects of monetary expansion from underlying investment dynamics.

Public Policy and Cost-Benefit Analysis

Cost-benefit analysis in public investment requires discounting future benefits and costs to present value. This directly descends from Fisher’s intertemporal framework, though debates persist about the ethical implications of discounting long-term outcomes such as climate change.

Conclusion

Irving Fisher’s The Theory of Interest represents a landmark in economic thought. It resolved long-standing disputes by uniting subjective time preference and objective productivity theories into a coherent equilibrium framework. Its insights into intertemporal choice, investment opportunities, and the real–nominal distinction remain central to economics and finance today.

Its limitations—particularly the assumptions of foresight, rationality, and the neglect of institutions—were exposed by Keynes and later theorists. Yet, these criticisms do not diminish its enduring significance. Fisher provided the intellectual scaffolding upon which modern intertemporal economics, financial theory, and central banking were built.

The work endures because it captured a universal economic truth: interest is the price of time. By framing economic life as a series of intertemporal choices, Fisher changed how economists, policymakers, and investors think about saving, investing, and consuming across time. Few works in economics have had such broad and lasting impact.

Select Bibliography

Fisher, Irving. The Theory of Interest. New York: Macmillan, 1930.

Fisher, Irving. The Rate of Interest. New York: Macmillan, 1907.

Fisher, Irving. The Nature of Capital and Income. New York: Macmillan, 1906.

Blaug, Mark. Economic Theory in Retrospect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Dimand, Robert W. Irving Fisher. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1993.

Hicks, J.R. Value and Capital. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939.

Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Macmillan, 1936.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. History of Economic Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954.

Tobin, James. “Irving Fisher.” In Ten Great Economists, edited by Joseph Dorfman, 195–222. New York: Columbia University Press, 1965.